(Source: Center for International Maritime Security – Colin Barnard*) – IMPROVE U.S. MARITIME POSTURE IN EUROPE THROUGH STRATEGIC REALIGNMENT

In July 2020, senior U.S. military leaders announced a realignment of the U.S. strategic posture in Europe, projecting the movement of troops and materiel from various locations in Germany to elsewhere in Europe and back to the United States. General Tod Wolters, commander of U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and NATO’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), argued the realignment enhances deterrence against Russia. Conversely, a former commander of EUCOM and SHAPE, retired Admiral Jim Stavridis, called the realignment a “victory for Putin.”

With President Biden’s defense team set to review the realignment during the 120-day period granted under the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, it is worth evaluating, which, if either, of the above statements is correct. I argue that the planned realignment should go forward, but only if it includes improvements to the U.S. maritime posture, including: additional forward basing for U.S. warships, better collaboration with NATO on maritime domain awareness, and more U.S. foreign area officers embedded in the NATO command and force structures.

The Benefits of Realignment

The potential benefits of the planned realignment should be easy for the Biden team to identify. Relocating EUCOM headquarters from Germany to near SHAPE’s headquarters in Belgium would, as General Wolters stated, “improve the speed and clarity of…decision making and promote greater operational alignment” of U.S. and NATO forces. Currently, General Wolters has to fly between these two headquarters just to address his staffs in person. While this is merely an inconvenience in peacetime, it is an unnecessary burden that could be dangerous during crisis or conflict.

Another benefit is the movement of air forces from Germany to Italy, closer to their parent headquarters and in a better position for operations across the Black Sea region and the Mediterranean. Russia’s continued presence in Ukraine, Georgia, and Syria, and its expanding footprint in Libya, warrant attention from both U.S. and NATO forces in Europe and highlight the need to think beyond the traditional notion of a front line with Russia that only faces eastward.

Perhaps the greatest benefit of the realignment, however, is the movement of 1,000 troops to Poland, raising the total U.S. troop presence there to 5,500. Defense cooperation between the United States and Poland—a key NATO ally that borders the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad and the infamous Suwalki Gap, and has an important coastline on the Baltic Sea—is crucial for deterring Russia. Additionally, the United States has recently improved on defense cooperation agreements with Sweden, Finland, Ukraine, and Georgia.

Along with these bilateral agreements, Biden’s team should also consider NATO’s collective deterrence efforts—for example, two forward presence initiatives implemented by NATO in 2016, which placed four battalion-sized battlegroups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland.

What is still inadequate in U.S. bilateral and NATO deterrence efforts, however, is the maritime domain. Deterrence and defense against Russia require more than just ground troops. It is a multi-domain effort requiring significant maritime forces. (…)

U.S. military presence in Europe continues to be necessary, but what that presence looks like, and where it is, should always be subject to reassessment. Security environments are not static, nor are the threats within them. During its review of the realignment, Biden’s team should keep a multi-domain focus when determining the right mix of forces forward deployed in Europe while taking into account existing NATO deterrence initiatives and the challenges posed by Russia at sea. (…)

*Colin Barnard is a U.S. Navy foreign area officer currently in training for an exchange with the German Navy. He was formerly a staff operations and plans officer at NATO Maritime Command in the U.K. In addition to publishing for the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings and the Center for International Maritime Security, he is a PhD student at King’s College London with a focus on European maritime security. The views expressed in this publication are the author’s and do not imply endorsement by the U.S. Defense Department or U.S. Navy.

Read Full Article >>> http://cimsec.org

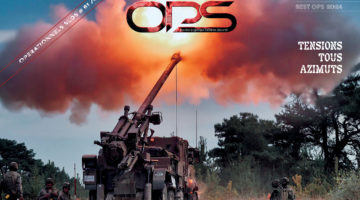

Photo © NATO’s Standing Maritime Groups Operating In the Mediterranean, as published in ibid