By Murielle Delaporte – Towards A Reconfiguration of French led Counter-Terrorism Operations In Sahel* [* A previous version of this article has been published by Breaking Defense on March 25,2022 >>> https://breakingdefense.com/2022/03/did-france-retreat-from-mali-its-not-that-simple-generals-say/ ]

On February 17th, President Macron officially announced the end of the French military presence in Mali, a decision motivated by the deterioration of Franco-Malian relations in the aftermath of the May 2021 coup d’état, but which does not stand for the failure of the counter-terrorism strategy led in that part of the world since 2013.

Introducing Wagner in the game

Having fomenting the fall of Ibrahim Boucabar Keïtar in August 2020, Assimi Goïta, then vice president and head of the junta seized power last May capturing President Bah N’daw, Prime Minister Moctar Ouane and Minister of Defence Souleymane Doucouré.

Sixty years after the first cooperation agreement was signed between Mali and the USSR in February 1961, following the Mali federation’s independence from France in June 1960[1], the Mali government has once again been seeking the help of the Russians to train and equip its forces in lieu of the French. Not the Soviet army this time, but the infamous Russian paramilitary organization Wagner, which has already been setting foot in Central African Republic over the past four years.

‘’In recent years, Wagner Group contractors have been deployed across the Middle East and Africa, including to Syria, Yemen, Libya, Sudan, Mozambique, Madagascar, Central African Republic, and Mali, focusing principally on protecting the ruling or emerging governing elites and critical infrastructures’’ stresses a recent report by the Brookings Institution[2].

In Mali, the number of Russian mercenaries is believed to have grown from about 40 in December to close to 1,000 today, taking over in particular the Timbuktu military installations recently transferred by the French military to the Malian armed forces.

As neighboring countries have watched such a pattern of military coups followed by a growing Wagner mercenaries footprint, they have become wary of a snowball effect and are determined not to follow this path. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted sanctions against the Malian junta last January[3], because satisfying calendar was set to conduct a democratic transition. These sanctions drove the latter to hinder more and more the action of the multinational forces initially deployed to fight terrorism ever since Bamako almost felt in the hands of the jihadists in January 2013, in particular by denying flight authorizations or drone use over parts of Mali territory and of course by using disinformation.

These multinational forces came from a virtuous ‘’dynamic of mobilization of partners built over the years’’ to fight terrorism in the region upon request of the Sahelian countries and including Mali, explains general Cyril Carcy, former deputy commander of the Barkhane Force. They include:

- the Barkhane force which stemmed from the Serval operation in 2014 ;

- the MINUSMA, i.e. the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali ;

- the EUTM, i.e. the European Union Training Mission in Mali ;

- and more recently the Task Force Takuba created in March 2020 : the TF is integrated to the command of Barkhane in order to fight terrorist groups in the three borders region (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger). Such initiative had received the support of the governments of Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Hungary and Italy and has led to the deployment in Mali of the special forces of 11 European nations.

‘’Other African countries do not like the Malian drift consisting in holding on to power. In this background and due to multiple obstructions by the Malian transitional authorities, we are bound to deplore that the political framework and necessary conditions to continue the fight against armed terrorist groups alongside the Malian armed forces, are no longer present. ’’, pursues Carcy, ‘’and this is the key reason, why, in concertation with all its allies, France – along with its partners from the Takuba task Force – has decided to leave Mali and redeploy’’.

Leaving does not mean the end of the fight

Such a departure from Mali should not however neither be compared to Afghanistan, nor interpreted as the end of the Barkhane mission. In many ways it follows the tradition of France’s past military operations and constant redeployments which have always evolved and adapted to the threat and the political changes on the African continent.

‘’The French Chief of Staff refers to it as a repositioning of our force posture’’, confirms the general. ‘’The fight against the terrorist groups is going to be pursued at the request and with the support of the neighboring countries, in particular Niger and Burkina Faso, while our presence will be enhanced in Western African countries, i.e. Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Benin and Togo’’.

The repositioning will be co-built with local European partners. Indeed Niger, where French and US troops have already been working side by side in Niamey and Ouallam for years, will likely play an important role of the future operation and Barkhane could change its name…

The ‘’spirit of Takuba’’ is also to remain as the majority of European contributors have renewed their commitment to continue the fight, after recording its first great operational success on the ground early February with the neutralization of 40 jihadists and huge volume of explosives.

At its peak Barkhane included 5,100 troops and it is estimated that 125,000 French soldiers have been deployed overall in Sahel in the past nine years. About 4,200 French troops are currently part of an operation covering the five countries of the G5-Sahel and should be limited to 2,500 within the next six months.

The mission will be focusing more on ‘’assisting, advising and accompanying local forces in Niger and Burkina Faso, and assisting and advising in the Guinea Gulf countries. That means that the level of ambition doesn’t change, but it will require less “French boots on the ground” as the French soldiers will fight, shoulder to shoulder with their partners and allies, but will not be as much at the forefront as they have been up till now. The goal is to keep eliminating the remaining threat of terrorist groups – JNIM (Al Qaeda) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (Daesh) in Niger and JNIM in Burkina Faso – and training Nigerien and Burkinabe armed forces so they can redeploy in areas controlled by the terrorists’’.

Indeed leaving Mali has a bitter taste for the French soldiers who fought there for years, losing more than 50 brothers in arms or being touched in their own flesh. France paid the blood money on the Malian soil. EUTM, the European Training Mission, which is planning to stay in Mali, and Barkhane have achieved a gigantic effort in training an Army which was not only poorly trained and equipped, but grew from 7,000 men to 40,000 today. ‘’Wagner is going to inherit all that…’’, notes the former Deputy Commander, stressing however that the Russians may encounter difficulties to hold such a vast territory in the long run, as it requires more manpower.

But for all that, the French authorities point out that the record of these nine years in Mali have brought a lot of successes ranging from the elimination of many terrorists and their chain of command (e.g. the recent neutralization of Al Qaeda’s chiefs Abdelmalek Droukdal in February 2020 or ISGS’s Adnan Abou Walid al Sahraoui in August 2021) to the conduct of numerous development projects. International aid flowing in the G5-Sahel is indeed currently reaching $2 billion a year.

Lastly, illustrating the fact that CT operations remain a major priority, on the night of February 25-26, 2022, the Barkhane force conducted a successful operation targeting an Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) senior leader and historic player in the spread of jihadist threat in West Africa, approximately 50 miles North of Timbuktu, in Mali. The operation led to the neutralization of the Algerian jihadist Yahia Djouadi, also known as Abu Ammar al Jazairi.

‘’Development and enhancing security via the training of armed forces are key to contain chaos and terrorist threat, a recipe which will be implemented in Mali’s neighboring countries. At the end of the day, you need to provide the youth with a different perspective than joining a jihadist group. That means creating stability, allowing the return of the state and creating development projects in the areas the Barkhane force has been freeing from the jihadists. All these steps take time and need strategic patience!’’, concludes general Carcy.

Footnotes

[1] See for instance >>> https://www.cairn.info/revue-bulletin-de-l-institut-pierre-renouvin-2017-1-page-83.htm

[2] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/08/russias-wagner-group-in-africa-influence-commercial-concessions-rights-violations-and-counterinsurgency-failure/

[3] https://african.business/2022/01/trade-investment/ecowas-imposes-sanctions-on-mali/

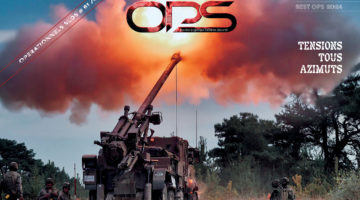

Photo © Niamey Base during Barkhane, Murielle Delaporte, Niger, 2015