By Julia Salabert, fellow intern at the Atlantic Council (« Young global professional / Transatlantic Security Initiative ») – Will NATO 5% defense spending pledge save the European continent?

Following Donald Trump’s return to the US presidency in 2025 and his ambition to make NATO alliances “fairer”[1] and prevent NATO European member states from ‘free-riding’[2] the Alliance, this article revisits the conceptual and strategic dynamics of NATO burden-sharing. It analyzes the political significance of NATO’s newly adopted 5% defense spending pledge, i.e. a 3.5% GDP commitment to core defense and an additional 1.5% to complementary security capabilities. It evaluates the continued relevance and shortcomings of the GDP target in light of shifting transatlantic power dynamics.

The 2024 US elections have significantly reshaped the global geopolitical landscape. The return to office of Republican Donald Trump reignited longstanding anxieties in Europe regarding the reliability of US commitments to NATO[3]. In late 2024, a few weeks only before his reelection, President Trump made regulat headlines in the media [4]. His comments triggered widespread international concern, with figures like John Bolton[5] suggesting a second Trump term could mark a ‘tipping point’ for US disengagement from NATO. European policymakers foresaw a genuine threat to the credibility of NATO’s collective defense principle.

At the same time, NATO leaders convened at the 2025 The Hague Summit and endorsed a new defense investment pledge.[6] This raises the defense spending benchmark from the long-standing 2% of GDP to 5%,[7] consisting of 3.5% dedicated to core defense expenditures and 1.5% allocated to broader defense-related and resilience investments. This move was widely interpreted as a strategic concession to Trump’s demands—originally floated during his first term[8]—and an effort to retain US engagement within the Alliance.

A TRANS-PARTISAN AND HISTORICAL TROPE

The US President’s statement must be historically and politically recontextualized. First, despite political instrumentalization, the US call for increased defense spending by European allies is not a partisan issue. In a different tone, former Democrat US President Barack Obama already called on Europeans to strengthen their defense budgets, emphasizing that “NATO will not be complacent”[9] and highlighting the necessity to “invest more in our common defense.”[10]

This trope is also historically recurrent. In the 1950s, President Eisenhower complained about the disproportionate defense burden the United States bore. He even accused the Western Europeans of “making a sucker out of Uncle Sam.” By the second half of the 1980s, there was a “widespread view that the status quo in NATO was disadvantageous for the United States,”[11] and European nations were already perceived as ‘free riders.’ While Trump’s discourse on the EU and NATO is uniquely brutal, his arguments fall in line with a longstanding American stance that European allies “need to do more to earn America’s protection.”[12] This narrative suggests calls for imminent US withdrawal from NATO[13] has actually been a persistent trope in Transatlantic relations. Constant mention of a crisis narrative in EU-US relations may then better be understood as a performative strategy to catalyze EU action rather than indicating a new radical US strategy.

RECALLING NATO’S FOUNDING STRATEGIC CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Cold War scholar Calleo analyses an initial “fundamental conflict of strategic interests”[14] between the US and European nations to shed light on the historical complexity that has grown within this principle of NATO’s burden sharing. The original purpose of NATO was to safeguard Europe from a Soviet attack by leveraging US nuclear capabilities. However, the rapid evolution towards nuclear parity with the USSR forced the United States away from the “massive retaliation” principle and into a “flexible response” policy. It advocated for confining any potential European conflict to conventional warfare as the most adequate way to avoid a worldwide nuclear armageddon. This conflicted with the European stance, which favored the nuclear warfare automatic escalation principle, considering only it ensured the European continent’s territorial integrity.[15] Recognizing this strategic divergence helps us understand the initial imbalance between the US’s considerable investment in conventional military capabilities compared to some European countries.

The debate on NATO’s conventional warfare burden-sharing spending has resurged nowadays, notably because of the Russian War of Aggression in Ukraine [16] Trump’s insistence on European NATO members “paying their bill”[17] does not refer to the participation in the actual NATO headquarters functioning cost, but the claim that each member state meets its GDP defense spending benchmark, now increased to a 5% goal following the 2025 NATO summit. This target officially aims to ensure a fair distribution of defense expenditures among NATO members and improve NATO’s defense posture against evolving global threats.

NATO DEFENSE SPENDING BLATANT IMBALANCE

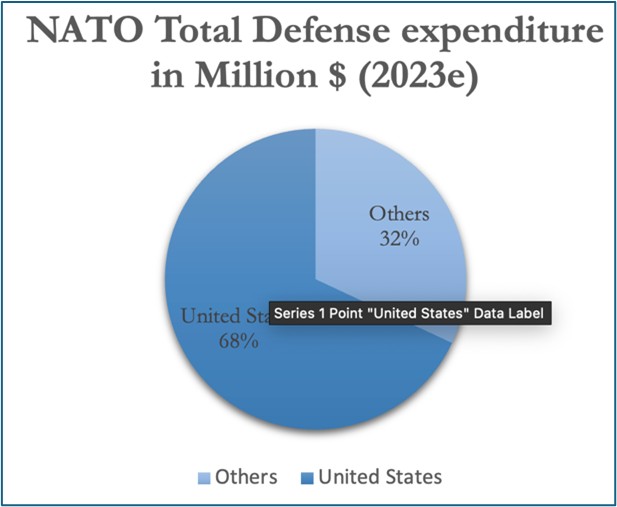

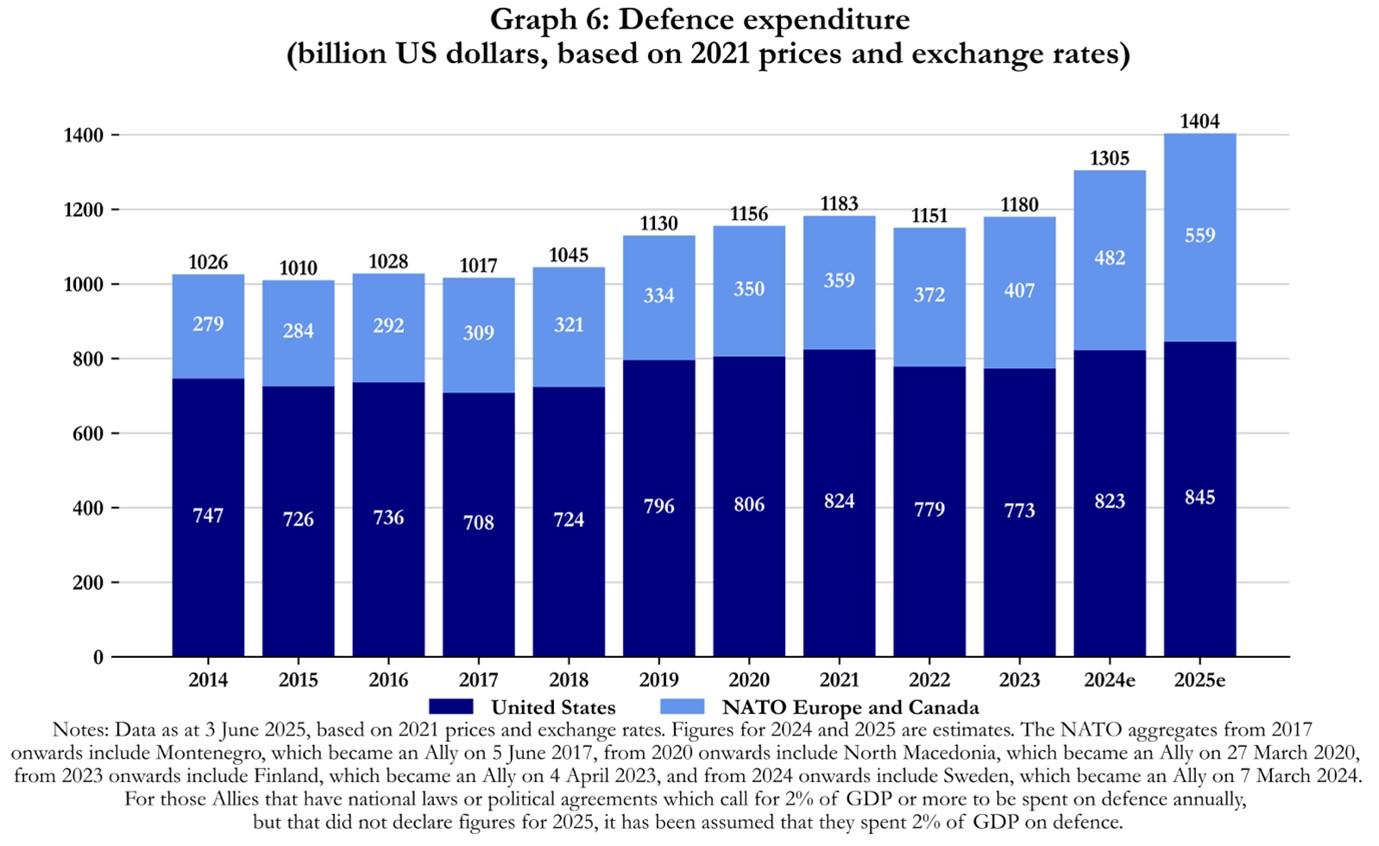

Allegations pointing out that European NATO members contribute less financially than the United States are empirically validated by defense spending data. In 2023, the combined defense expenditure of all non-US NATO members constituted merely 32% of the total NATO defense expenditure, with the US accounting for the remaining 68%.

United States: 860 000 Others: 404 115

Notes: The figure is based on official NATO data.

This numbers imbalance remained despite an increase in defense expenditure by NATO Europe and Canada of 100.4 % between 2014 and 2025. Meanwhile, the US increased its defense spending by approximately +13% during the same period.

EU MEMBERS GEAR UP THEIR DEFENSE LEVEL

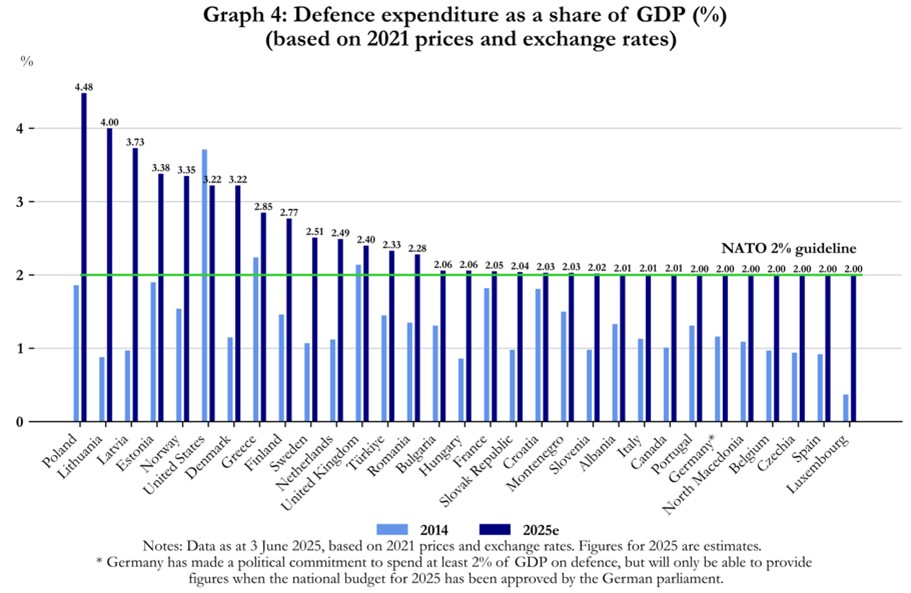

However, “this does not mean that the US is being taken advantage of.”[18] As we can see, in relative terms, non-US members’ defense spending has significantly increased. By the end of 2025, all European NATO members will have achieved the 2% collective GDP target set at the 2014 Wales summit. With the 2025 shift to a 5% investment pledge, member states are now expected to further scale their efforts by 2035

CONCEPTUAL LIMITS OF THE 2% TARGET RULE

While this achievement is politically significant, doubts remain about whether this solves the issue of unequal burden-sharing, as “serious doubts have been cast over the value of 2 percent as a useful metric.”[19] While “[serving] as a proxy through which a much larger geopolitical issue is being tackled”[20] from within the Alliance, this pledge is criticized for merely focusing on financial inputs rather than military outputs.[21] Specific spending of GDP on defense provides limited indications of a military’s readiness, deployability, sustainability, and quality. Furthermore, the metric fails to consider a country’s strategic decision-making regarding the allocation of resources or its willingness to deploy troops and assume political risks for it. Thus, the 2% may not reflect a country’s defense spending effectiveness.[22]

Budgetary Considerations

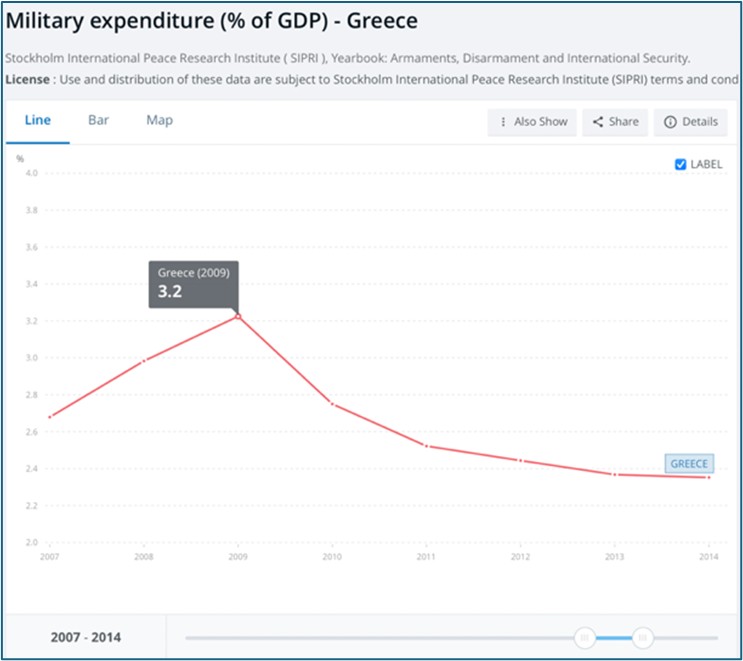

First, although widely mobilized, the GDP-based metric for defense spending does not account for the economic variations across countries, rendering the defense budget vulnerable to national economic fluctuations rather than indicative of deliberate strategic defense planning or capabilities.[23] This phenomenon has been seen during the Eurozone crisis, for instance, when Greece’s defense budget escalated from 2.7% of GDP in 2007 to 3.2% in 2009 before decreasing to 2.4% in 2014.

Nature of defense spending

Furthermore, the focus on allocating 5% of GDP to defense does not account for the nature of such spending. There is no shared understanding of what “military expenditure” represents among member states. NATO’s definition notably includes military pensions[24]—a significant portion of several countries’ defense budgets—without directly adding value to military operational capabilities. In 2016, for example, pensions accounted for 33% of Belgium’s, 24% of France’s, and 17% of Germany’s defense budgets. While these expenditures contribute towards meeting the GDP target, they do not help increase combat effectiveness.[25] Similarly, questions remain over the broader definition used in the new 5% pledge. The inclusion of infrastructure resilience, cybersecurity, and other non-military domains under the 1.5% category may introduce discrepancies and creative accounting among allies—possibly reinforcing rather than reducing burden-sharing ambiguities.

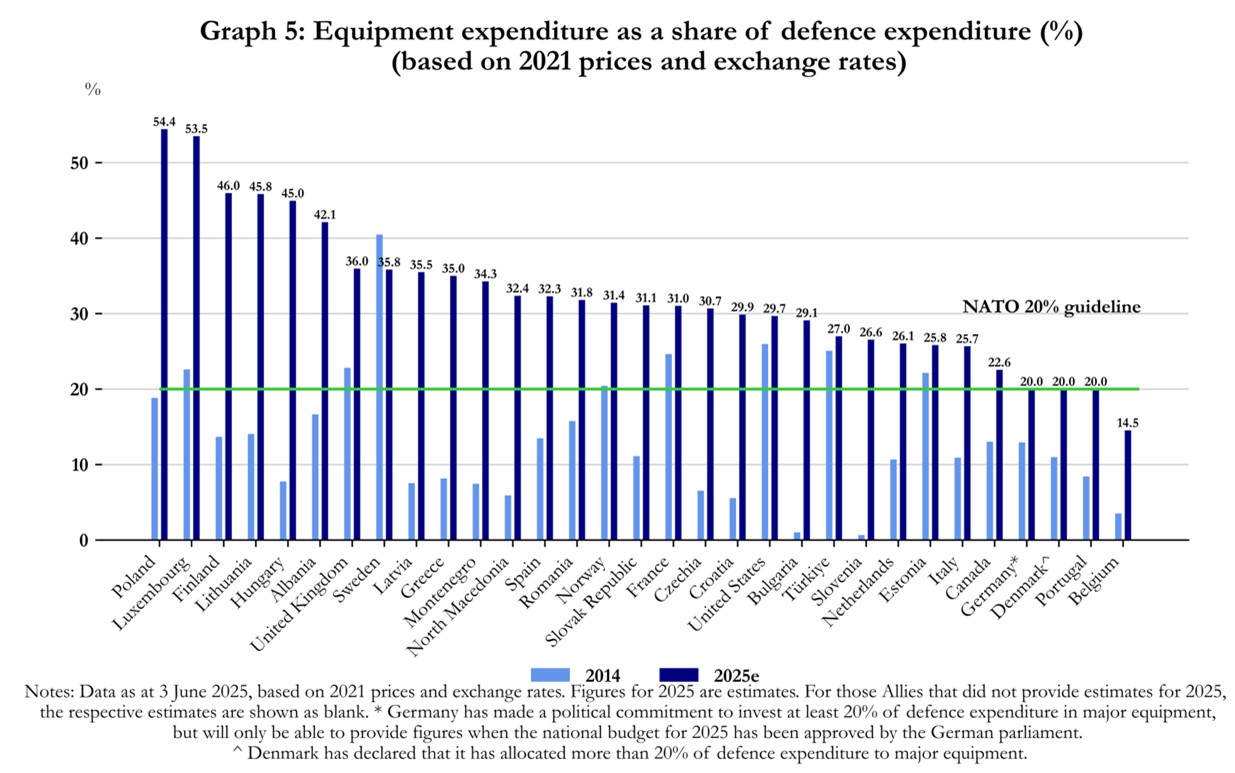

Quality vs. Quantity

Besides, the metric overlooks the importance of military research and development investment, which may be equally— or more—valuable to NATO’s collective defense. The 20% target guideline for equipment expenditure as a percentage of defense spending is a valuable complement, giving insight into the country’s defense innovation.[26] The figure above provides a much different spending distribution, with Poland, Luxembourg, and Finland coming top of the countries in equipment expenditure as a share of defense expenditure, and the US meeting Croatia’s percentage around 30%.

IN SEARCH OF AN ACCURATE ENGAGEMENT ASSESSMENT TOOL

Given these considerations, the 2% target seems more symbolic than realistic for assessing a country’s defense commitment or capabilities. Moreover, should members fail to meet this target, it could become counterproductive and put institutional credibility at risk for NATO by inadvertently highlighting perceived member states’ disengagement, without accounting for the complexities of defense preparation.[27] Spain’s refusal to abide by the new NATO pledge has thus attracted much criticism, despite its long-lasting involvement in collective defense mechanisms.[28] The new 5% framework, while more flexible and expansive, might deepen rather than resolve such ambiguities unless clearly defined and rigorously audited.

Nevertheless, despite its conceptual flaws, the GDP metric remains remarkably mobilized. That could implies its political utility, particularly for the US in maintaining influence within NATO, arguably overshadows the metric’s technical shortcomings. A clear and impactful way of targeting alleged free riders might be instrumental in the US retaining its leadership position.

As EU members increase their military capacity and refocus toward more active participation in collective defense, this will inevitably increase their expectation of strategic influence within the Alliance. This evolution towards a more balanced partnership should be carefully crafted to aim toward a coherent transatlantic Indo-Pacific strategy, while benefiting the Alliance as a whole by raising its defense readiness. However, “if the EU [was] to take over from the US in leading […] NATO, it is unclear what such leadership would look like and what it would prioritize.”[29]

Notes & references

[1] Donald Trump Tells Nato Allies to Pay up at Brussels Talks, BBC edition, May 25, 2017, BBC Edition, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-40037776.

[2] Jason Davidson, No ‘Free-Riding’ Here: European Defense Spending Defies US Critics, March 13, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/no-free-riding-here-european-defense-spending-defies-us-critics/.

[3] David E. Sanger and Maggie Haberman, “Donald Trump Sets Conditions for Defending NATO Allies Against Attack,” The New York Times, July 21, 2016, sec. US, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/21/us/politics/donald-trump-issues.html.

[4] Jill Colvin, Trump Says He Told NATO Ally to Spend More on Defense or He Would ‘Encourage’ Russia to ‘Do Whatever the Hell They Want,’ PBS News Hour edition, February 11, 2024, PBS News Hour Edition, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/trump-says-he-told-nato-ally-to-spend-more-on-defense-or-he-would-encourage-russia-to-do-whatever-the-hell-they-want.

[5] “John Bolton: Trump Will Pull US out of NATO If Reelected,” DW, February 27, 2024, https://www.dw.com/en/john-bolton-trump-will-pull-us-out-of-nato-if-reelected/video-68382326.

[6] NATO, The Hague Summit Declaration Issued by the NATO Heads of State and Government Participating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in The Hague 25 June 2025 (2025), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_236705.htm.

[7] NATO, “Defence Expenditures and NATO’s 2% Guideline,” February 20, 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49198.htm.

[8] “Donald Trump Veut Que Les Pays de l’OTAN Augmentent Leur Budget de Défense à 5 % Du PIB,” Le Monde Avec AFP, January 7, 2025, https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2025/01/07/donald-trump-veut-que-les-pays-de-l-otan-augmentent-leur-budget-de-defense-a-5-du-pib_6486929_3210.html.

[9] The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, “Remarks by President Obama at NATO Summit Press Conference,” September 5, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/05/remarks-president-obama-nato-summit-press-conference.

[10] President Barack Obama, “America’s Alliance with Britain and Europe Will Endure,” July 2016, https://pl.usembassy.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2016/07/obama_oped.pdf.

[11] David P. Calleo, “The American Role in NATO,” Journal of International Affairs 43, no. 1 (1989): 19–28, JSTOR.

[12] Jens Ringsmose and Mark Webber, “Hedging Their Bets? The Case for a European Pillar in NATO,” Defence Studies 20, no. 4 (2020): 295–317, https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2020.1823835.

[13] Michael E. O’Hanlon, “Trump Courts Real Danger with His Invitation to Attack NATO,” Brookings, February 15, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/trump-courts-real-danger-with-his-invitation-to-attack-nato/.

[14] Calleo, “The American Role in NATO.”

[15] Calleo, “The American Role in NATO.”

[16] Craisor-Constantin Constantin Ionita, “Conventional and Hybrid Actions in the Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” Security and Defence Quarterly, ahead of print, August 15, 2023, https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/168870.

[17] Matt Berg, “Trump Says NATO Countries Spent ‘Billions’ after He Threatened to Not Defend EU,” POLITICO, January 20, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/2024/01/20/trump-nato-eu-00136732.

[18] Johannes Thimm, “NATO: US Strategic Dominance and Unequal Burden-Sharing Are Two Sides of the Same Coin,” Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik (SWP), April 9, 2018, https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/nato-us-strategic-dominance-and-unequal-burden-sharing-are-two-sides-of-the-same-coin.

[19] Jan Techau, The Politics Of 2 Percent. NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe (Carnegie Europe, 2015), https://carnegieendowment.org/files/CP_252_Techau_NATO_Final.pdf.

[20] Techau, The Politics Of 2 Percent. NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe.

[21] Techau, The Politics Of 2 Percent. NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe.

[22] Claudia Major, “Time to Scrap NATO’s 2 Percent Pledge?,” April 28, 2015, https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/59918.

[23] Minister of Canadian National Defence Anita Anand, “Is Canada a ‘Military Free-Rider in NATO’?,” July 15, 2023, CBC News, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPCdsGM2JqY.

[24] NATO, “Defence Expenditures and NATO’s 2% Guideline.”

[25] Lucie Béraud-Sudreau and Bastian Giegerich, “Counting to Two: Analysing the NATO Defence-Spending Target,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), February 28, 2017, http://felipesahagun.es/counting-to-two-analysing-the-nato-defence-spending-target/.

[26] Techau, The Politics Of 2 Percent. NATO and the Security Vacuum in Europe.

[27] John Dowdy, “More Tooth, Less Tail: Getting beyond NATO’s 2 Percent Rule,” McKinsey & Company, November 29, 2017, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/more-tooth-less-tail-getting-beyond-natos-2-percent-rule.

[28] Andrew Gray et al., NATO Agrees to Higher Defence Spending Goal, Spain Says It Is Opting Out, June 23, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/nato-countries-approve-hague-summit-statement-with-5-defence-spending-goal-2025-06-22/.

[29] Roberta N. Haar, “Why America Should Continue to Lead NATO,” Atlantisch Perspectief 44, no. 2 (2020): 31–37, JSTOR.

Illustration © AI generated