From the Hudson Institute – The Russia-Ukraine war has highlighted the security dilemmas of Eurasian countries that find themselves outside of any regional military alliance.

Although recent attention has focused on Ukraine, the Caspian littoral countries have, for several years, considered themselves vulnerable to renewed Russian assertiveness and have complained about declining U.S. and European engagement in their region.

In response to these challenges, as well as in pursuit of new opportunities for regional energy cooperation, Azerbaijan and Turkey have partnered with Georgia, Iran, or Turkmenistan in recent years to pursue targeted trilateral economic, energy, and security collaboration.

The trilateral format, most often seen in meetings of the three countries’ foreign ministers, supplements bilateral and other multilateral mechanisms and helps the participants advance their national security, economic development, and geopolitical independence.

The Caspian triangles also enable these states to achieve diplomatic compartmentalization and manage antagonistic relationships by aligning with different combinations of partners in pursuit of mutually beneficial goals.

Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Georgia

The most developed of the Caspian trilateral partnerships is that among Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Georgia.

These three states have enjoyed good relations since the breakup of the Soviet Union, but they only formalized their trilateral cooperation following the 2006 opening of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and the August 2008 Russian-Georgian War, which challenged their mutual economic and security interests.

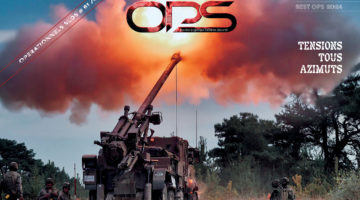

Since then, the three countries have built additional energy pipelines, a trans-Caucasus railway, and undertaken joint military exercises.

Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Iran

Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Iran represent a more complex Caspian triangle.

The three countries’ foreign ministers have discussed various regional energy, investment, transportation, and security projects since their first meeting in April 2011.

Mutual distrust, regional rivalries, international sanctions and other obstacles have impeded realization of most initiatives.

As a result, the parties have concentrated on making incremental progress now, while hoping to expand their partnership should more favorable conditions arise, such as following a nuclear deal that ended most international sanctions.

Given Iran’s poor relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey, this trilateral construct has also aimed to manage their differences in a conflict-prone region.

Past tensions have centered on Ankara’s and Tehran’s backing of opposing local actors in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, and Iranian concerns about Azerbaijan’s secular and Western orientation.

Azerbaijan, Turkey and Turkmenistan

The foreign ministers of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Turkmenistan only began meeting last year.

This triangle has focused on promoting economic cooperation, but energy and security collaboration may follow.

In particular, Turkey would like Turkmenistan to send gas westward through the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline.

However, the unresolved territorial dispute between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan over several energy deposits in the Caspian Sea, as well as other constraints on Ashgabat’s foreign policy flexibility, limit this triangle from realizing its potential.

The Lynchpin

Turkey and Azerbaijan form the linchpin of the three triangles.

Turkey needs more energy sources and wants to become a bridge between Europe and Asia, while Azerbaijan seeks to expand its regional energy and security connections.

The two countries share cultural, religious, and ethnic ties – Azeris are a Turkic people.

The official discourse of both countries highlights their special relationship, which is ascribed to historical, ethnic, cultural and other ties, by referring to them as “one nation” living in two states.

In a regional context, ties with Turkey strengthen Azerbaijan’s position in negotiations on Caspian energy and transit projects.

Without Turkey’s participation in the triangles, Azerbaijan has much less to offer Georgia, Iran, and Turkmenistan.

The Caspian triangles stand out as one of the few successful Turkish foreign policy initiatives in recent years.

Through its economic and political cooperation with Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkmenistan, Turkey amplifies its regional economic and security influence in the South Caucuses and the Caspian Basin.

Ankara also establishes itself as an important transit corridor and energy hub between the Caspian countries and Europe, which has become even more important with the Ukraine crisis.

Although Ankara’s ties with Tehran remain troubled, the triangle reduces the prospects of a military confrontation between Iran and Azerbaijan that could easily drag in Turkey and other countries, like Russia.

The remaining Caspian triangle countries are excluded from the Washington-led NATO alliance, the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization, and other regional security structures. Although Ankara remains in NATO, Turkish policy makers fret about their limited influence on the European Union’s security policies.

Turkey’s efforts to develop alternative ties with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) have been stymied due to Russian-Turkish differences over Syria and other tensions.

Although Iran has observer status in the SCO, Beijing and Moscow have made clear that Tehran’s prospects for full membership depend on a resolution of its nuclear dispute. Whereas Azerbaijan and Georgia are most interested in bolstering their Euro-Atlantic orientation, Iran and Turkmenistan are also eager to strengthen ties with China.

While none of these governments characterize their Caspian triangles as being directed against any country, the partnerships increase their independence from Russia without their aligning with other great powers, like China and the United States.

The trilateral framework facilitates cooperation without compromising diplomat flexibility.

Pursuing trilateral partnerships offers an advantage over bilateral alliances since participants can cooperate with neighboring states without having to negotiate formal alliances that could compromise their members’ independence, national identity, or other strategic relationships.

The triangles are easy to create but also to dissolve as the goals of each partner naturally evolves.

Nonetheless, the unresolved dispute over maritime boundaries and usage rights in the Caspian Sea remains a major constraint on realizing the Caspian triangles’ energy potential.

Not only have the littoral states failed to resolve their overlapping territorial claims, but Russia and Iran have vetoed trans-Caspian energy pipelines by insisting that all five littoral states must approve their construction.

The lukewarm U.S. and European support for trans-Caspian projects has also limited the triangles’ impact.

The West has strained relations with all five governments directly involved in the triangles, as well as with many other Eurasian states. Western governments and NGOs have criticized the Caspian countries’ restrictions on political pluralism and free market principles. For their part, the five governments participating in the Caspian triangles have complained about insufficient Western respect and support for their interests and values.

Western governments need to look past these differences and recognize that these trilateral partnerships can enhance Eurasian-European energy collaboration, discourage Iranian and Russian predatory behavior, and stabilize a region primed for problems.

Photo Credit: The defense ministers of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey met in August 2014 and agreed to work on “tripartite exercises to enhance the combat capability of the armed forces of the three countries and the achievement of mutual understanding during joint military operations, including the organization of joint seminars and conferences, cooperation in military education, development of military technology, the exercises for the protection of oil and gas pipelines,” according to Azerbaijani Defense Minister Zakir Hasanov (>>> http://www.eurasianet.org/node/69646)