By Murielle Delaporte – This is a long version of an article published in Breaking Defense.

If NATO regularly reviews its strategic concept like it is currently the case with NATO2030, it will be the very first time that the European Union will actually adopt what it is calling a ‘”Strategic Compass’’ during the first semester of 2022. Initiated under the German presidency of the Council of the European Union in 2020, such a document will be adopted under the French presidency.

Indeed, the French minister of the armed forces, Florence Parly, participated on April 23rd to a European Union defense ministers workshop on the ‘’Strategic Compass’’. Organized in Lisbon by the Council of the European Union such a meeting is presented as a preparation for the future European White Paper. An opportunity for France to confirm its commitment to have the latter become a “genuine roadmap towards a more sovereign Europe” based on four main points: crisis management, resilience, capabilities and partnerships.

At a time of increased instability, such a development is significative in itself as an effort to promote a ‘’common strategic culture’’, shared threat assessment and above all a common course of action. If all Allies agree with President Biden for the need to ‘’chart a new course’’, while ‘’the alliances, institutions, agreements, and norms underwriting the international order the United States helped to establish are being tested’’, as stated in the March interim document, there are obvious differences in the way it should be translated into action whenever a crisis occurs.

Both Germany and France are among the nations traditionally conducting White Papers as a preliminary analysis towards their military programming laws. In 2017 and in view of the aggravation of domestic and international security concerns, France decided to opt for a “Strategic Review” rather than a White Paper, which would be written by a committee rather than a commission in 3 months and a half rather than a year.

Four years after this first and only strategic review so far, the Macron government decided it was necessary to update the last edition with a ‘’strategic-update 2021“. The sense of urgency came from what the French government and outside experts, who contributed to the review in collaboration with some allies’ counterparts, perceive as a genuine risk for Europe to be totally left out from a ‘’disinhibited strategic competition’’ not only by big powers, but also by emboldened regional powers such as Turkey and Iran : ‘’today, the risk of a definitive downgrade, nay even of an erasing of the European continent in world affairs, cannot be avoided anymore’’, says the official document presented by the minister of the Armed forces to the latter last January.

If the assessment of recent French – and European efforts in general – to catch up with the gap left by decades of benign neglect as far as military expenditures are concerned, is not overly concerning, the current pandemic has brought with it the ‘’worst world economic recession since 1929’’. The major question mark is therefore the sustainability by most European countries to keep up with the surge in military capabilities which had been underway before Covid.

France has decided to pursue both in terms of personnel and equipment such an effort for the duration of the current Military Programing Law 2019-2025 (at least till 2022 of course given the upcoming Presidential elections). The French ministry of the armed forces indeed just announced on April 15th its decision to accelerate some procurement deadlines in order to help with the post-pandemic recovery with the early order of 8 caracal H225M helicopters. Used by both the Army and the Air Force and in particular by the French special forces, the Caracal is the only helicopter in Europe that can be refueled in flight. The 300 million euros investment is aimed at containing the current aeronautic crisis and sustaining 960 jobs for Airbus Helicopters, Thales, Safran and their suppliers over three years.

Such an effort regarding the respect of the military budget (an unusual habit actually) has a double focus: modernizing both nuclear and conventional forces considered the two complementary pillars of French defense and security policy on the one hand, pursuing what is referred to as a ‘’complete armed forces model’’ capable of intervening no matter what kind of threat France may face on the other hand.

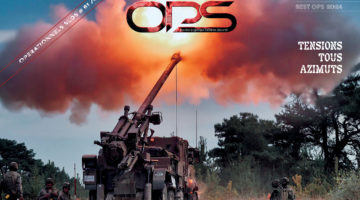

The traditional ‘’tous azimuts’’principle seems indeed even more relevant today than ever given the alarming evolution of the risks now ‘’at the doorsteps of Europe’’. From the deconstruction of the international order to new forms of ‘’muted subversion’’, from new imbalances (demographic in particular) to a new global cartography of resources in the making (in part due to climate change), from the instrumentalization of migratory flows (the way Turkey did recently) to the end of taboos in the use of massive destruction weapons – whether NRBC (e.g. Syrian use of chemical weapons) or the ‘’end of the classic nuclear codes of deterrence’’ -, the 55-page update is very precise about the range of new threats – high-end or hybrid – joining of course the ‘’old’’ ones, such as terrorism and the risks of new Islamic states popping up in unstable areas.

Facing also new types of threats in their nature like all Western nations, the French government has been very steady in developing brand new strategies in domains now considered crucial such as cyber (in 2018), space (in 2019), artificial intelligence (2019), long range power projection (associated with a new Indopacific strategy also in 2019), and finally energy (in 2020). It intends to pursue investments meant to enhance France and European strategic autonomy in particular in game-changing domains and breakthrough technologies, such as artificial intelligence.

If Covid has – like everywhere else – awakened French leaders to stress sovereignty and put an end to the excesses of globalization especially as far as the defense industrial base is concerned, the goal is the ‘’creation of mutual dependencies with partners (…) agreed upon as opposed to be subjected to’’. The rise of China as the second military power and a ‘’systemic rival’’ of Europe is indeed clearly highlighted in the French document. The way to deal with the Chinese threat will probably be one of the most difficult question for Europe to address in its 2022 ‘’Strategic Compass’’, but progress towards a common threat analysis picture is starting to emerge on some out of area theaters : European countries not traditionally familiar with Africa or the Med from a military point of view have been participating in European joint operations such as EMASOH, the European-led Maritime Awareness mission in the Strait of Hormuz which just celebrated its first year of existence, or the TAKUBA task force which gathers the special forces of seven European countries to train and accompany Malian forces in the fight terrorism in Sahel.

An impetus sometimes considered modest by many observers and critics, but a growth nonetheless and not to be underestimated given the multi-front risks and threats both the United States and Europe now face. Being able to be present and holding on together to assist nations in parts of the world where the vacuum will be immediately filled by hostile powers are already a major achievement when the very nature and existence of our models of society are under siege…

Illustration © https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/bulletin-article/2020/can-eus-strategic-compass-steer-european-defence