10 février 2012 – Vu sur le web en anglais

Le Centre britannique de recherche sur les blessures provoquées par explosion – le « Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies » – a mis au point un nouveau simulateur appelé ANUBIS (« Anti-vehicle Underbelly Blast Injury Simulator ») permettant de déterminer l’impact d’une explosion par IED au niveau du bas-ventre, une blessure particulièrement difficile à soigner et dont peu de combattants touchés se remettent. L’espoir est de parvenir a faire dévier l’impact vers une zone où une chirurgie reconstructive s’avèrerait possible.

source : www.defenceiq.com

Voir l’article original ci-dessous >>

—————————–

Explosive look into world’s leading IED blast lab:

By Andrew Elwell

Posted: 02/09/2012 on www.defenceiq.com

Defence IQ was recently given a tour of Imperial College London’s IED blast research lab, known as the Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies. In this, the first of a two part interview, Professor Anthony Bull, the Centre’s Director, explains why it was established and provides an insight into the sort of cutting-edge science taking place at the College.

“The reason why we want to do this now is because so many people who previously died as a result of these kind of injuries are now surviving. That’s as a result of medical technology and significant improvements in logistics over the past few years, so that’s the good news. The bad news of course is that lots of people are now maimed in a way that we previously haven’t seen. So we need to do something about it.”

In a recent study of the Armoured Vehicle market 2012 – 2022, respondents were asked to define which threats the military should seek to protect against most “when considering the future battlespace.” Both commercial (95%) and military respondents (89%) identified the IED as the most critical threat. If that wasn’t evidence enough, those respondents that added a comment were unequivocal, simply stating: “IEDs, IEDs, IEDs.” It’s clear that all other threats, though clear and present, must be considered ancillary to the biggest killer on the frontlines and backstreets: IEDs.

There’s little doubt the work being carried out at the RBL Centre at Imperial College is of critical importance then. The truth is we (medical science, military personnel, the royal we) have never before seen the sort of injuries that IEDs cause, such is their devastating impact. The Imperial College blast lab’s mission is to investigate these physical and biological insults in order to begin understanding them and, hopefully, to moderate their effects.

“Part of the story is really about understanding those injuries better because there are some physical responses we haven’t seen before, that medical science hasn’t seen before, and there’s also some biological responses that we’ve never seen before,” Bull said. “So there is both a scientific and a medical opportunity to do something which has never been done before.”

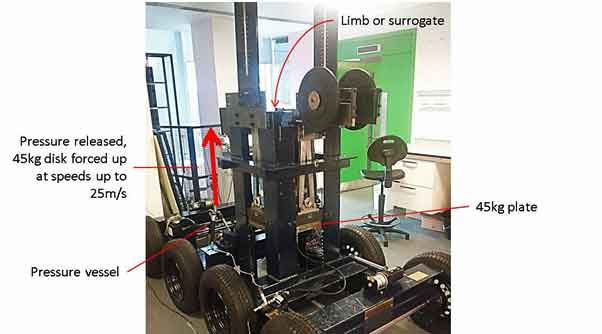

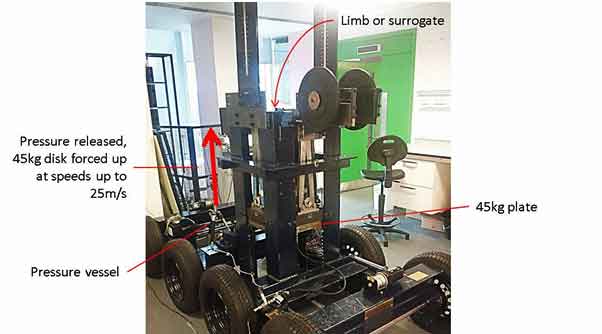

The Centre has received a £5 million grant from RBL as well as a £3 million package from Imperial College itself. The showpiece of the lab is ANUBIS (Anti-vehicle Underbelly Blast Injury Simulator), which is “a large lump of metal … that simulates an explosion underneath the vehicle and how the vehicle deforms onto the human body,” Bull tells us. By experimenting with ANUBIS Bull explained that they can collect and analyse data to understand how best to mitigate both the blast and the injuries sustained as a result.

“By mitigation we mean not stopping what happens during the blast absolutely, but maybe deflect the injury or biological response to something that is more amenable to repair or to recovery,” Bull says. “For example, there are certain types of musculoskeletal injuries, which are injuries to the bones and joints, that cause long-term disability, result in multi operations and re-operations and we know that the end effect will be something severe like an amputation a couple of years down the line. But we also know that certain other injuries that might look more severe when they first happen actually are amenable to repair. And so that knowledge in and of itself and the tools that we’re developing here at the Centre will allow us to creatively explore ways of deflecting the blast or the encroachment of the vehicle, whatever it may be, the injury, to an area that’s more amenable to reconstruction. We think that’s possible and that’s the kind of thing we’re working on here.”

ANUBIS

Professor Bull talks us through how ANUBIS works.

“In the middle here we have a heavy disk that weighs about 45 kg. Through a pressure vessel underneath we can increase the pressure where at a certain load the plate will be released to accelerate upwards and in a couple of milliseconds it will be at maximum velocity, which we can vary up to about 25 m/sec. Although actually to replicate the kind of injuries we see in the human body from the battlefield currently we only need about 9 m/sec which is what we’ve been doing.

“So this shoots up and these four sets of breaking bars then stop it from going through the ceiling. We then mount the human tissues – which have been donated for this research and approved by an ethics committee – in a seated position, where the foot sits on the bottom plate. We can also simulate the standing position and anything in between. We’ve also used crash test dummies, or surrogates as they’re called. In fact the word surrogate is a useful one to use because we also have computational surrogates and this machine allows us to verify our computer models which can simulate the same kind of insult on the human body.”

Stay tuned next week for Part 2 of this interview with Prof. Bull where he discusses the Centre’s future direction, potential commercial applications for the Centre’s work, and much more beside.