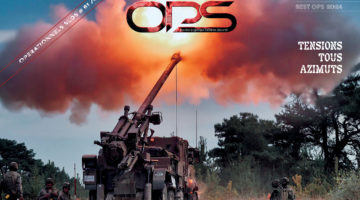

Photo credit © French Army

By Stig Jarle Hansen, Associate, Senior Analyst, Risk Intelligence

Overview

Since the French intervention early in 2013, the Mali conflict has been a defining one for regional security. The intervention itself was successful in the short run.

Territorial integrity was more or less restored by the end of 2013, and expectations directed towards the new president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, are high.

The military gains of the various Islamist forces in Mali have been undone.

But the area cannot be entirely controlled and a low-level insurgency campaign may be able to operate with relative impunity at least in the short term.

Operation Serval

As early as February 2013, the French-led operations as part of ‘Operation Serval’ attacked the Ifoghas mountains and rebel strongholds around Gao. At the peak, 4,000 French soldiers and around 7,000 troops from various West African countries in the so-called African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) were in action.

However, the Islamists did not actively fight the international alliance, understanding that they had no possible chance of withstanding them, but resorted to guerrilla war and terrorism. The terror attacks included suicide bombing: on 30 March 2013, the city of Timbuktu was attacked when a suicide bomber blew himself up at a Malian army checkpoint.

On 12 April, two suicide bombers detonated their belts near a group of Chadian soldiers in a busy market in Kidal. Overall, the military campaign proved relatively successful. France subsequently withdrew a portion of its forces, indicating that only 1,000 men would remain after April 2014. AFISMA was turned into a United Nations mission: United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, MINUSMA.

The size of this force was in theory set to 12,000, but it became hard to get contributions, the AFISMA being turned into MINUSMA almost en masse (with some few West African forces withdrawing elements), with minor contributions from the West. The forces lacked air mobility, with few air assets, in a land with large stretches of desert and wilderness, but helped oversee a successful election, as well as peace agreements with the various non-Islamist oppositional forces, including the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). The international and Malian forces even managed to kill off Hacene Ould Khalill, also known as Jouleibib, the deputy commander of the infamous Those Who Sign In Blood Brigade.

However, the structural problems that at the start created the Mali rebellion are still there. There is a security vacuum in neighboring Niger and it seems, over the last months of 2013, that a reorganized alliance of Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s former part of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has unified with the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) to become al-Mourabitoun. Moreover, the mistakes that initially created the space for the Islamists – an unjust, fragmented and corrupt state structure, more an arena for clashing elites and predation than a modern state – might be recreated, as indicated by the promotion of former Malian officers involved in the coup.

It should be remembered that the Islamist takeover from the north was caused by tensions between the government and the northerners, with the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) taking advantage of the confusion after a coup in Bamako.

Will such a window of opportunity present itself again ?

It was initially created by an armed rebellion launched on 17 January 2012, enhanced by a military coup that deposed President Amadou Toumani Touré on 22 March the same year. However, structural conditions, relating to tribe, religion, and the quality of Malian institutions, created a weakness that made the explosion possible. Indeed, the rebellion can be seen as a continuation of the previous Tuareg rebellions taking place in Mali in 1962-64, 1991-1995, and 2007-2009. Tribal politics, Malian state inefficiency, and geographical challenges were all a problem, then as now.

The difference this time was the Islamist ideology that was spread into the country. Worth considering are the local conditions that enabled a situation that Islamists could take advantage of, while also noting the tribal mechanisms including among the Islamists themselves.

An institutional and tribal crisis ?

To understand the current situation in Mali, and indeed the neighboring countries, one has to understand the tribal, economic, and institutional foundations of the rebels. Indeed, the Malian crisis was partly created by an institutional crisis, as well as a crisis of clientelism in the Malian state and also the Malian army.

During the initial rebel campaign, Malian units feared their own commanders or at times did not expect actually to fight rebels because of the bonds of clientelism. The command and control system was hampered by these factors leading to very poor performance by the Malian army. Given that several of the old commanders, who were also behind the coup, have been re-instated, the question is whether we will actually see a new and more efficient army. Tribalism was a large factor in the conflict, as it has been before, as was class; even the Islamists had tribal/ clan connections.

In fact tribalism becomes a slightly misleading word because of the Tuaregs’ advanced tribal system, a system divided up into classes as well as tribes. The class system of the Tuaregs consists of the Imajaghan, the traditional ruling dynasty, a warrior and princely caste; the Imgad, the second warrior caste; the priestly Marabout or Inselmen class; the Inadan blacksmiths; and the farmers, Zeggaghan. There was also a slave caste. The two last castes were alien to the rebellion.

In addition to the caste system, the Tuaregs are also divided into clans, following a matrilineal pattern. In other words, your mother’s tribe is your tribe, although the tribal leaders are always men.

Each clan consists of various castes, although sometimes, as in Mali, several castes are geographically separated from each other. In the case of Mali, the rebellion to a certain extent was a Kel Adagh rebellion (var. Kel Adrar, Kel Adghagh, less commonly Kel Ifoghas: meaning ‘those from the mountains’ in Tamasheq, a local variation of the Tuareg language, and also a clan federation). The majority of the tribe was made up of the Imajagahan and the Imgad castes. The Tuareg group that launched the rebellion, the MNLA, hailed from the Kel Adagh and fought, in a pattern common in Malian history, against what they felt was suppression of Tuaregs, but also for independence.

They were soon to be outflanked by another Tuareg movement hailing from the same clan but from different sub-clans, the Ansar Dine. This was led by a Tuareg chieftain, Iyad AgGhali. It was perhaps Ansar Dine that was different from the previous Tuareg rebellions in 1963, 1990, 1993-1994(in Gao), 2006, and 2007-2009. From 2009 and onwards, stronger Islamist factions appeared on the battlefield; in2012 they gained widespread control.

The role of Islam

The Islamization of parts of the Tuareg rebellion, and the turning south of AQIM, contributed a new dimension to the usual center–periphery (or rather center–Tuareg) conflicts of Mali. AQIM was in itself an Algerian organization officially affiliated to al-Qaeda in 2007. However, its members had immunity in Mali as a consequence ofa deal freeing 32 Western hostages mediated by Iyad AgGhali and sanctioned by the Malian state in 2003.

This gave safety to local representatives, who increasingly became married into Malian society. Mokhtar Belmokhtar, for example, married an Arab woman from Timbuktu. AQIM gained much wealth from border smuggling and kidnapping operations, which enabled them to buy off the Malian police and army.

By 2005, AQIM operations were striking into Mauritania as well, and by 2011 also Niger. According to claims by Al Jazeera, a separate entity recruited in Mali and Mauritania, the al-Furqan Squadron led by the Algerian Jamal Akasha,was established, The parts of al-Qaeda acted quite independently, but some central control might have been reasserted when AQIM sent a new leader to the area in 2007.

Fragmentation, at times across ethnic lines, continued to plague the organization; the most serious was when SultanOuld Baddy, a former smuggler also known as AbuAli, split off, allegedly after wanting to have his own ethnically defined forces made up of Arab Azawad. In December2011, the new organization of MUJAO, composed mostly of southern Saharans, emerged from within its ranks. Baddy was joined by Mauritanian activist HamadaOuld Mohamed al-Khair, also known as Abu Qaqa. The organization at the start recruited mostly from the Arab Lamhar tribe (also known as Ahmar), attempting, often very successfully, to sway fighters from this tribe away from al-Qaeda.

The tension between the two was quite great, but Mokhtar Belmokhtar intervened in order to make peace. The organizations became able to co-ordinate and, although the claim is speculative, Belmokhtar might have had more sympathy with Baddy than his nominal leaders to the north. MUJAO briefly held Gao in 2012, and actively tried to promote law and order based on the sharia. It reportedly managed to transcend its initially ethnic foundations by recruiting among the Songhais, presenting a law and order alternative to the more secular Tuareg militias, which often raped and pillaged.

There were many rumors that were hard to assess, for example that the organization recruited more members from smaller villages famous for stricter practices. The last piece in the Islamist trinity was Ansar Dine, led by Iyad Ag Ghali, also known as Abou El Fadl, veteran Tuareg rebel leader, and indeed a traditional leader from the Ifoghas. He was crucial in the Tuareg rebellion of the early 1990s, but joined the government. He had also acted as intermediary between the government andal-Qaeda in hostage situations in the 2000s.

Allegedly, he had become more religious when encountering the Jama’at al-Da’wa wa al-Tabligh, becoming more inspired by them from 2000 onwards. Iyad Ag Ghali had previously been known to enjoy a drink now and then. Some sources, including reports from Time magazine, claim that it was tribal rivalries that led to Iyad Ag Ghali creating Ansar, after he failed to gain the traditional leadership of the Ifoghas.

This might be true, but would be hard to confirm. Ansar Dine was locally focused, and often mentioned sharia implementation as its main target. It also managed to get a foothold amongst the Berabiche Arabs from the Timbuktu area. Ansar’s tribal link means that it is more vulnerable, and that parts of it are only loosely Islamist. Ifoghas have also joined because of family networks, for the lure of profit, and for career opportunities for both former Tuareg nationalists and former al-Qaeda junior commanders, such as Sanda Ould Boumana. Ansar Dine could also take advantage of the prominent profile of AQIM, because other factions declared the latter a primary opponent.

The three Islamist organizations all had definitive criminal connections. Indeed, in a first wave of analysis they had been depicted as almost criminal, profit-based organizations.

However, after the In Amenas attack in Algeria, several analysts suggested that all of them took advantage of illegal arms trade, smuggling, and even drug trafficking to harness resources for jihad. The reality is probably a combination: with profitability often comes corruption.

What about the Islamist trinity today ?

Although many analysts are reluctant to trust the info, it seems logical that relations between Belmokhtar’s units of AQIM and MUJAO would grow more intense, partly because of increased estrangement between Belmokhtar and AQIM. By August 2013, Operation Serval had disrupted the operations of the trinity, and it was claimed to have inflicted 400-600 casualties. A large number of fighters switched sides, but many stayed in the Islamist organisations to continue fighting.

In Gao, MUJAO still has strong roots partly because of tribal links. Observers have also speculated whether the various Islamist organisations could seek shelter in Niger, Chador Libya, countries in which territorial control of the Saharan area is of a random type. In Libya, it seems that the pattern of Tuareg areas and location of refugees from al-Qaeda match each other, with al-Qaeda being based in the valleys of the Akkakush mountains north of the town of Ghat. At the same time there are indications of some Nigerian presence in Mali, as posters promoting the Nigerian jihadists of Ansaru and reports of Nigerian participants start to appear.

Meanwhile there are rumours emerging of recruits coming to the Islamists from countries to the north and as refugees from Western Sahara. In Mali, other cleavages might still create a window of opportunity for these organizations.

The more secular Tuaregmilitias, the MNLA and the Azawad Arab Movement (MAA), only have an interim peace agreement with the government and have not disarmed. A final federalised solution has yet to be implemented.

A new conflict between the government and MNLA and MAA might still occur, although the presence of the international coalition calms the situation down, and the threat of such a scenarios diminished by the frequent interaction between these organizations and the new government.

What is the potential for the Islamists ?

The vacuum of the Sahel cannot be filled, as the neighboring states lack the capacity to control the area fully, although in the end technology might make insurgent operations harder. The chaos in Libya also allows al-Qaeda veterans as well as Ansar Dine and al-Mourabitoun jihadist refugees to find refuge, and the Ifoghas Mountains can still provide some shelter.

On the other hand, the French and West African forces inside Mali cannot be beaten in open battle in Mali: the organizations are relegated to guerrilla fighting. They could be able to keep themselves alive for years in this manner; they would probably not be fully defeated, rather controlled and kept from capturing territories. Given this, and the porous borders of the region, as well as the capacities of the regional powers, the security situation will remain unstable. Al-Mourabitoun is definitively threat against oil installations in the whole region.

The vastness of the deserts and the traditional mobile fighting style of the group will ensure that it can penetrate far into the territories of Niger, Mauritania, Algeria and Libya. This will be the case in the foreseeable future, and canine fact only be stopped by an increased regional aerial surveillance capacity, a capacity that is not currently near the level needed to prevent such activities.

It is also highly likely that the group will resume kidnapping activities. Al-Mourabitoun will, however, not be able to take and hold territories in any of the region’s countries, nor will it probably be able to establish larger training camps. It may also be vulnerable to targeted attacks, such as the apparent operation by French Special Forces in April 2014 that targeted the leader of al-Mourabitoun, Abubakral-Nasri.

The fragility of regional governments, with their general failure to curtail Islamist activities, means that analyses of the capacities of these governments and their security services should be conducted in any good risk plan. It is not any longer good enough to assume, as several companies before the In Amenas incident did, that local authorities would provide security.

This piece was republished with the permission of our partner Risk Intelligence. To subscribe to their regular publication Strategic Insights please go their website

This piece was first published in the July 2014 issue.